Public Sphere

Public Opinion and the ability to discuss public life in a public sphere was nascent and only coalesced into existence in the past 300 years. Before then, the feudal system and the Church’s influence limited the potential to discuss issues publicly. Jurgen Hambermas states that “It is not possible to demonstrate the existence of a public sphere in its own right, separate· from the private sphere, in the European society of the High Middle Ages” (Thornham et al., 2009)

In France, the church held sway over public opinion until their Revolution; when public opinion forced the separation of the Church from the state.

While some countries still hold their Church’s opinions highly (Russia and Poland as examples) the power the Church wields over doctrine and public opinion has begun to wane. Technology and global communication allows new public opinions to be broadcast into other public spheres that may have otherwise remained controlled, accepted and unchallenged by the public in that country.

For instance, the forced public sphere of a despotic regime such as North Korea controls this influx of ideas via the internet (or as Koreans know it Kwangmyong) by tightly restricting access to Kwangmyong. Including controlling access to it by its citizens that travel abroad. With harsh penalties for those caught breaking this rule.

In the rest of the world, ideology and public opinion were tightly controlled by “The feudal powers (the church, the prince, and the nobility)” (Thornham et al., 2009).

They ideologies were seen as a statement of fact. Dissent or discussion was not tolerated. And was manipulated by a sophisticated system of public opinion management. Contrary views were heretical and ex-communication and even death were used as the ultimate sanctions should members of the public express any opinions in the public sphere that were deemed to be contrary to accepted dogma.

This status quo began to change with the proliferation of coffee houses in London in the 1700s. These allowed the public to discuss the issues of the day unhindered. In a time when the printed word was becoming widespread with newspapers and journals becoming available. The public sphere expanded as new bourgeois public opinion was allowed to grow, through argument, discussion and even some eventual consensus. This emerging bourgeois class were now able to discuss all matters of common interest and therefore allow private citizens to come together as a “public” and freely discuss whatever subjects they chose.

This new level of expression was seen as dangerous from the ruling elite’s viewpoint as it interfered with the long-standing tradition of control over the public sphere and public opinion. So much so that the government sent spies into this new debating arena on suspicion that sedition was fermenting.

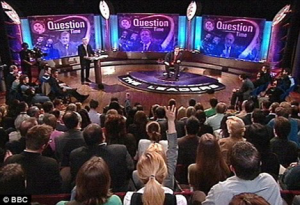

The UK’s political system now allows free speech and for public opinion to be openly debated in various public spheres. Television programmes such as the Question Time allow for public opinion to be formed through debate.

References

Ellis, M. (2008). An introduction to the coffee-house: A discursive model. Language & Communication, [online] 28(2). Available at: https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.brighton.ac.uk/science/article/pii/S0271530908000062 [Accessed 18 Feb. 2018].

Kim, J. (2017). North Korea Bans Overseas Citizens from Mobile Internet. [online] Radio Free Asia. Available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/korea/internet-03072017143412.html [Accessed 18 Feb. 2018].

Lee, D. (2012). Surfing the internet in North Korea. [online] BBC News. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-20445632 [Accessed 18 Feb. 2018].

Smith, P. (2018). London Coffehouses and Habermas’s ‘Public Sphere’.

Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAqAKmQElpY [Accessed 18 Feb. 2018].

Thornham, S., Bassett, C., Marris, P. and Habermas, J. (2009). Media studies. 1st ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, p.46.

Thornham, S., Bassett, C., Marris, P. and Habermas, J. (2009). Media studies. 1st ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, p.47.